Colorado health advocates presented to the Joint Budget Committee on glitch-plagued Public Health Emergency Unwind.

Recent articles

2024 Legislative session: addressing economic challenges at the individual and state level

Addressing economic challenges at the individual and state level after the 2024 Colorado legislative session.

CCLP’s 2024 legislative wrap-up, part 2

CCLP's 2024 legislative wrap-up focused on expanding access to justice, removing administrative burden, supporting progressive tax and wage policies, preserving affordable communities, and reducing health care costs. Part 2/2.

CCLP’s 2024 legislative wrap-up, part 1

CCLP's 2024 legislative wrap-up focused on expanding access to justice, removing administrative burden, supporting progressive tax and wage policies, preserving affordable communities, and reducing health care costs.

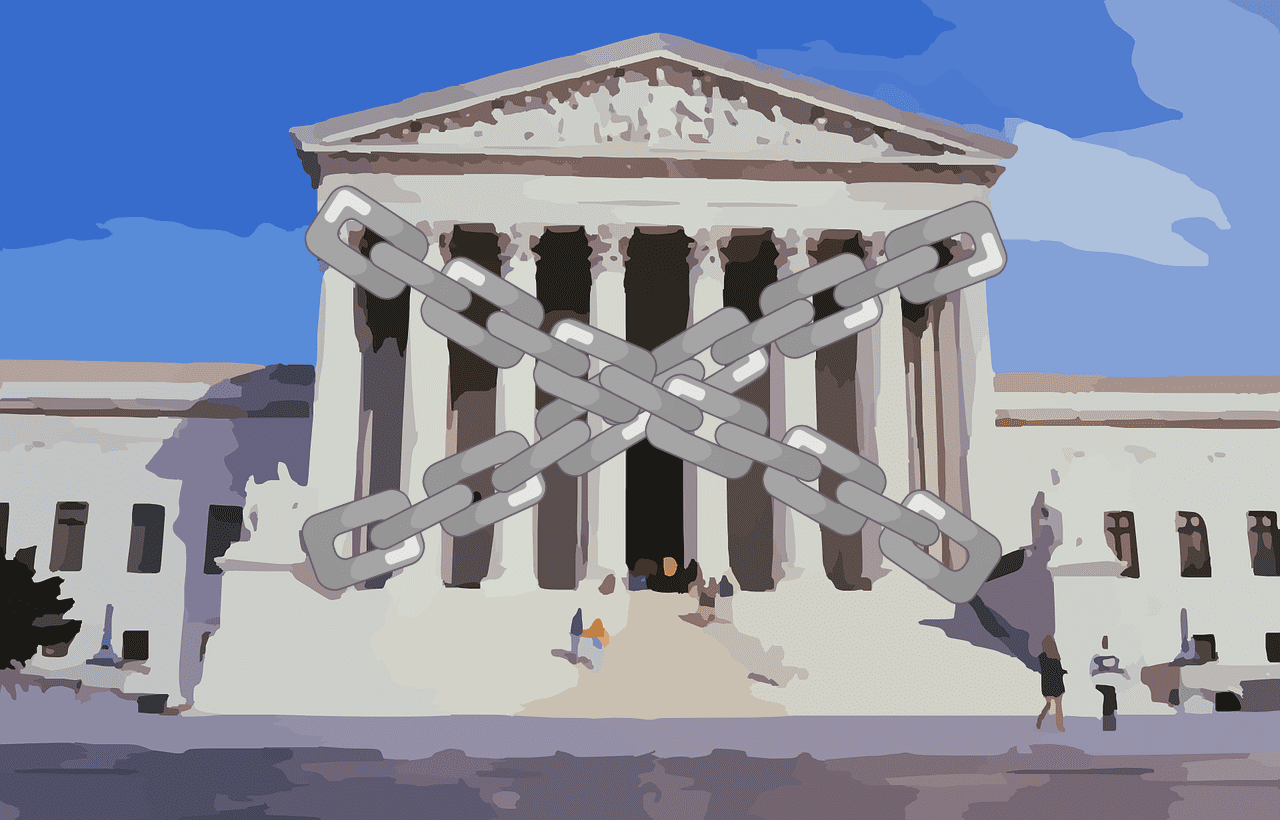

CCLP Statement on Health and Hospital Corporation v. Talevski

Last term, we watched as the Supreme Court issued rulings that had wide sweeping consequences for individuals across the country. The Court tipped its hat to the second amendment by expanding the ability to carry guns in public while simultaneously decimating the well-established right to privacy grounded in the fourteenth amendment.

One case that was less covered in the mainstream media, but that dealt a severe blow to civil rights practitioners, was Cummings v. Premier Rehab Keller, P.L.L.C. In short, that case involved a deaf and legally blind patient seeking physical therapy services from a facility in Texas that receives federal funds. The facility refused to provide American Sign Language interpretation, and the patient sued for emotional distress damages under the Rehabilitation Act and the Affordable Care Act.

The Court, relying on contract law, held that emotional distress damages are suddenly not available under laws passed under Congress’s “spending clause” authority, unless such damages are explicitly provided for in the law.

The Spending Clause of the U.S. Constitution in part gives Congress the ability to spend money for the “general welfare” of the United States. Often, this is in the form of “conditional grants,” like Medicaid, that give states money so long as the state complies with various federal requirements. So, for example, Cummings would foreclose emotional distress damages under the Rehabilitation Act, the Affordable Care Act, Title VI (prohibiting race discrimination), and Title IX (prohibiting sex discrimination in education).

Cummings provides a dismal look inside what might happen in the upcoming Supreme Court term with respect to enforcing certain laws.

On November 8, the Court will hear arguments in Health and Hospital Corporation v. Talevski. Talevski involves a nursing home resident who was given a high dose of psychotropic medications against his will and was repeatedly transferred to facilities far away from his family.

George Talevski’s family sued the nursing facility for violating federal law by relying on 42 U.S.C. § 1983 – a federal law that allows individuals to sue the government or state actors for civil rights or federal law violations. Section 1983 has consistently been used to ensure that state actors comply with constitutional provisions and federal statutes.

Nonetheless, the Court has agreed to consider the question of whether individuals harmed by an entity’s failure to follow federal spending clause legislation can sue to enforce their rights under section 1983.

The Medicaid Act is just one example of spending clause legislation that CCLP regularly relies on to hold state agencies and counties accountable. The Food Stamp Act is another. If the Supreme Court decides that private parties cannot sue to enforce these statutes, it will become increasingly difficult to truly ensure that state agencies are fully compliant with federal law.

We are right to be worried. Typically, when the Supreme Court agrees to hear a case, it means that there is a novel question of law, or there is some sort of disagreement among lower courts about how to interpret the law. The Court’s function is to resolve those disagreements and act as the ultimate decision maker.

But in this case, like the recent abortion decision of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, there is longstanding precedent allowing beneficiaries to enforce their rights in court and thus little disagreement among courts about the interpretation of Section 1983. It is therefore concerning that the Court is even considering the question.

Given the impact Talevski could have on Coloradan beneficiaries and CCLP’s ability to enforce public assistance laws, CCLP joined the National Health Law Program and forty-two other non-profit organizations in a “friend of the court” – or amicus curiae – brief to explain why the Court should not depart from precedent.

You can read the brief here.