Charles Brennan provided testimony in support of House Bill 24-1129, Protections for Delivery Network Company Drivers. CCLP is in support of HB24-1129.

Recent articles

CCLP testifies in support of TANF grant rule change

CCLP's Emeritus Advisor, Chaer Robert, provided written testimony in support of the CDHS rule on the COLA increase for TANF recipients. If the rule is adopted, the cost of living increase would go into effect on July 1, 2024.

CCLP testifies in support of updating protections for mobile home park residents

Charles Brennan provided testimony in support of House Bill 24-1294, Mobile Homes in Mobile Home Parks. CCLP is in support of HB24-1294.

CCLP’s legislative watch for April 5, 2024

For the 2024 legislative session, CCLP is keeping its eye on bills focused on expanding access to justice, removing administrative burden, preserving affordable communities, advocating for progressive tax and wage policies, and reducing health care costs.

Making cents of the headlines, part 2: What causes inflation?

Inflation numbers for December are out today. Prices of the goods included in the Consumer Price Index increased by 7.0 percent year-over-year in December 2021, a level not seen in 40 years. Excluding energy and food prices, which tend to be more volatile than other prices, core inflation last month was 5.5 percent.

While many policymakers and economists hoped the inflation we experienced over the course of 2021 would be transitory (economist-speak for “temporary”), the headline and core inflation rates continue to be well above the Federal Reserve Bank’s long-term target of 2.0 percent. Comparisons to the inflation our economy experienced during the 1970s are everywhere, as are warnings that the spending proposed as part of the Build Back Better Act (BBBA) will only make inflation trends worse.

Too often, however, pundits and doomsayers forget the basics: What really is inflation, why does it happen, and what factors are truly driving the inflation we currently see?

What is inflation and why does it happen?

Simply put, inflation is an increase in the prices consumers pay for the goods and services they buy.

While this definition helps us understand what inflation is, it does not tell us why inflation happens. To understand this, we must think about our economy in terms of two groups:

- Producers: the people or businesses who make goods or provide services

- Consumers: the people or businesses who buy those goods and services

In nearly all economic transactions, producers are the ones who set the price of their goods and services and consumers use their personal income to purchase them. If prices increase, it is because a producer decided to charge more for a good or service than they did previously.

Why would a producer choose to increase their prices?

There are many reasons why producers may choose to increase their prices:

- A producer may be a consumer themselves, purchasing their own goods (including raw materials) or services (including labor) in order to produce the good or service they intend to sell. Those purchases are called inputs. If the prices of the producer’s inputs increase, they might respond by raising their own prices, particularly if they want to continue earning the same profits from their enterprise.

- When many consumers in the economy see an increase in their incomes, producers may raise their prices knowing consumers have more money in their pockets and presumably can afford to pay more. Most consumers are willing to pay higher prices, so long as they can still buy the same amount of goods and services as before.

- When there aren’t many producers of a particular good or service in a sector or a market, such as in rural areas, producers may raise prices knowing consumers have limited alternatives, due to the lack of competition or availability of substitutes.

- Other times, producers of a good or service may be unable to ramp up production quickly enough to meet an unexpected increase in demand from consumers. Producers may then raise prices until production can increase, knowing that consumers will pay more for a scarce product and will try to out-bid one another in order to buy that good or service.

- Unforeseen events, such as a natural disaster or a labor strike, may disrupt the production of a good or service, preventing producers from supplying the same amount to consumers as they did before the event. As in the previous example, producers may then increase prices as consumers compete for a scarce product, at least until production is able to return to previous levels.[1]

While economists use fancy terms to describe the dynamics described above, such as demand-pull inflation, cost-push inflation, or expansion of the money supply, they are essentially saying the same thing. However, it is common to frame these causes of inflation as something that “just happens” in the market, ignoring the fact that markets are made up of people each making their own specific choices.

While this list is not exhaustive, these examples illustrate how inflation is a choice on the part of producers — NOT, as critics of BBBA argue, an inevitable outcome of federal government spending on social programs.

While economic conditions and government policies certainly influence the behavior of producers and consumers, it is the sum of the decisions of producers to charge more for their goods and services that ultimately results in inflation. This is not to say that producers are bad actors for raising prices—they may have very rational reasons for doing so. However, we cannot effectively address inflation unless we understand what is causing producers to raise prices.

For example, effective policy responses to price increases due to production disruptions (say, those caused by natural disasters) are entirely different from policy responses to price increases due to the monopoly power of a particular set of corporations.

How the Pandemic is contributing to inflation

The causes of the inflation we see today are many, and largely depend on the product or sector we are looking at. However, there are some general trends over the past two years that help us to understand what is happening today.

First, the COVID-19 virus caused our economy to come to a screeching halt, as stay-at-home orders, business closures, goods shortages, and job losses kept consumers in Colorado and the rest of the country from spending on goods and services. In response, the U.S. Congress passed a number of measures that provided income supports to households and businesses.

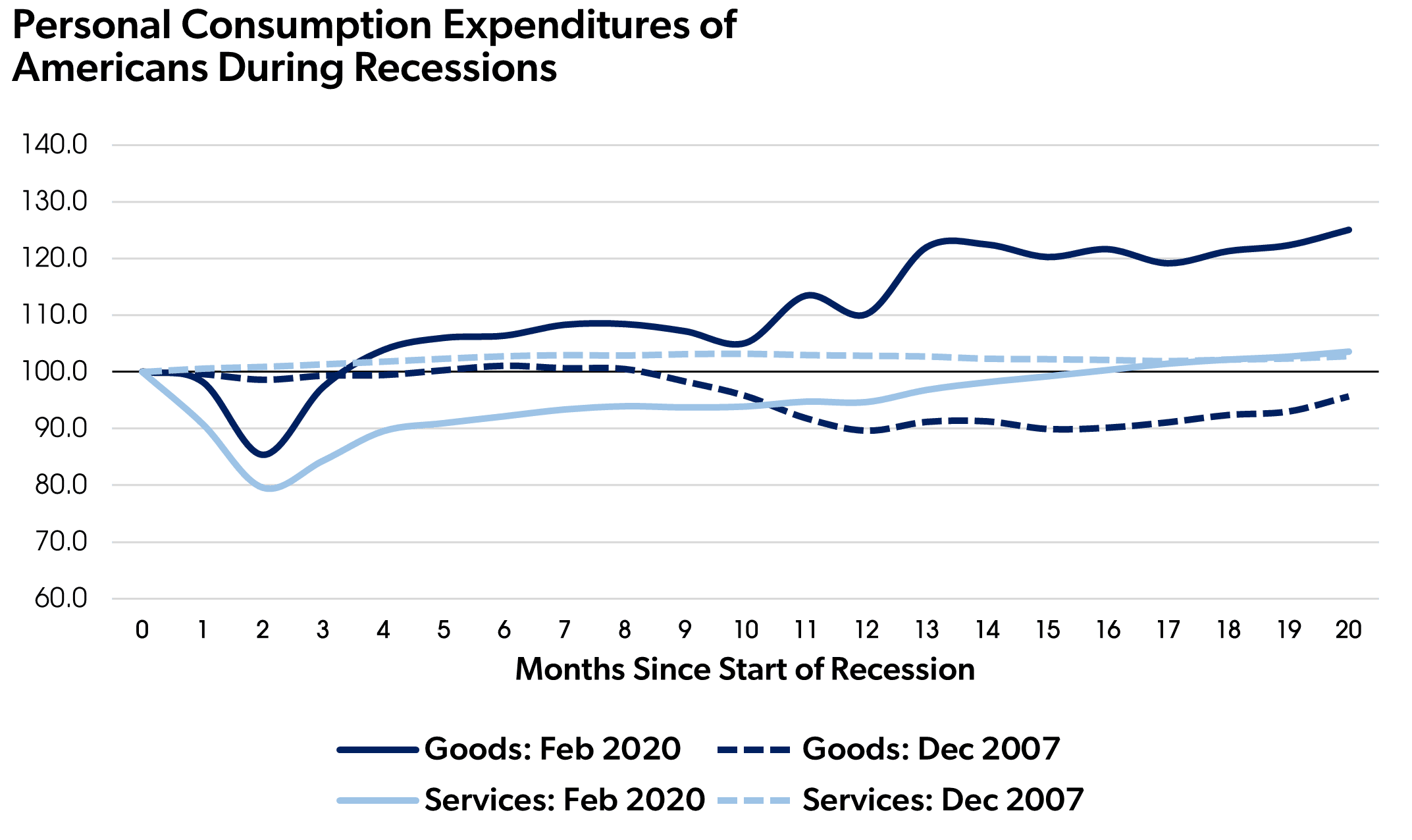

Once the economy began reopening in April 2020, consumer spending quickly recovered to pre-pandemic levels, thanks to these programs and to increased saving by many households. Due to the ongoing pandemic and public health restrictions on the economy, however, this spending skewed heavily towards goods instead of services.

Personal consumption expenditures on goods by American consumers returned to pre-pandemic levels by June 2020, something that took 38 months during our recovery from the Great Recession. Demand was further juiced in March 2021, when the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) provided an additional round of stimulus payments.

On the other hand, personal consumption expenditures on services didn’t return to pre-pandemic levels until June 2021, months after COVID-19 vaccines were widely available in the United States.[2]

Note: Values for expenditures on goods and services are indexed to December 2007 for the Great Recession and February 2020 for the COVID-19 recession. 100 represents expenditures levels in those months, respectively.

Source: Colorado Center on Law and Policy analysis of U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis Personal Consumption Expenditures data retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

While pandemic-related legislation gave a large boost to demand for goods among American consumers, the pandemic disrupted — and continues to disrupt — production and supply chains around the world. Due to decades of outsourcing, most of the goods purchased by American consumers relied on supply chains that extend around the world, making them vulnerable to disruptions from the pandemic and foreign governments’ responses to it.

For instance, pandemic-related shutdowns of semiconductor microchip factories in East Asia at the start of the pandemic led to disruptions in the supply of such chips, which are used widely in many electronic devices and appliances. Companies who produced goods that used these microchips, including automobile manufacturers, faced shortages once their stockpile of chips had been depleted. These shortages were exacerbated once production restarted to meet the roaring demand for goods among consumers in the United States and around the world.

Carmakers not only had to compete with one another for these chips, but also with a whole range of other producers and manufacturers who faced similarly high demand for their own goods, such as laptops. As chip shortages created a shortage in new automobiles, for example, the prices of both new and used cars increased dramatically.[3],[4]

A similar story exists for many other goods that experienced inflation over the course of the past year. These disruptions in the supply of goods are what economists mean when they talk about “supply chain disruptions”. In these instances, there is a mismatch between the amounts of goods producers are able to supply, and the amounts of goods consumers are demanding to buy.

Our economy is huge and is interdependent on the economies of countries around the world. Any changes in production will take some time to make an impact on the inflation we are experiencing today. Unfortunately, COVID-19, specifically the Omicron variant, continues to create disruptions in production processes around the world.

However, supply chain disruption is not the only cause we see today, and in fact there are other forces at play that are likely making inflation worse, particularly in industries and markets where corporate consolidation is enabling firms to use their market power to raise prices by an even greater amount than their own costs have risen.

If supply chain disruption were the sole source of inflation, we would expect to see corporate profits hold steady or potentially decline. Indeed, in many sectors, the very opposite is true. Large corporations have made record profits throughout the ongoing challenges of the pandemic. We will take a closer look at this trend in our next blog post in this series.

[1] For more on what causes inflation see:

Harvey, John T. “What Actually Causes Inflation (and who gains from it)?”. Forbes (2011). Access from https://www.forbes.com/sites/johntharvey/2011/05/30/what-actually-causes-inflation/?sh=3bf244f9f9a9 on 16 December 2021.

Mason, J.W. and Lauren Melodia. “Rethinking Inflation Policy: A Toolkit for Economic Recovery”. Roosevelt Institute (2021). Accessed from: https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/rethinking-inflation-policy-a-toolkit-for-economic-recovery/ on 16 December 2021.

[2] U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Personal Consumption Expenditures: Goods and Services, retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfred.org/series/PCES.

[3] Bellon, Tina and Paul Lienert, David Shepardson. “Inflation risk or profit engine? High car prices are both”. Reuters (August 2021). Accessed from: https://www.reuters.com/world/the-great-reboot/inflation-risk-or-profit-engine-high-car-prices-are-both-2021-08-10/ on 16 December 2021.

[4] “Explainer: Why is there a global chip shortage and why should you care?” Reuters (March 2021). Accessed from: https://www.reuters.com/article/chips-shortage-explainer-int/explainer-why-is-there-a-global-chip-shortage-and-why-should-you-care-idUSKBN2BN30J on 16 December 2021.