Charles Brennan provided testimony in support of HB26-1012, which would have required sellers to provide consumers with the prices of the delivered goods and the goods available at the store for price transparency and fairness. It also would have prohibited unfair or deceptive trade practices by charging unreasonably excessive prices for goods and services.

Recent articles

CCLP testifies in support of worker protections

Chris Nelson provided testimony in strong support of House Bill 26-1054, which would allow Colorado to step in to address declining workplace safety standards due to federal rollbacks and decline in enforcement, and allows for individual workers and labor unions to enforce their rights through private right of action.

CCLP testifies against HOAs requiring “proof of need” for language access

Morgan Turner provided testimony against HB26-1201 which would require owner's to provide "proof of need" prior to HOAs providing correspondence and notices in a language other than English.

CCLP testifies in support of ITINs for non-educational opportunities

Milena Tayah provided testimony in support of HB26-1143, which addresses the background check barrier for educational opportunities. It would require that an ITIN be allowed in lieu of a SSN when required for these background checks.

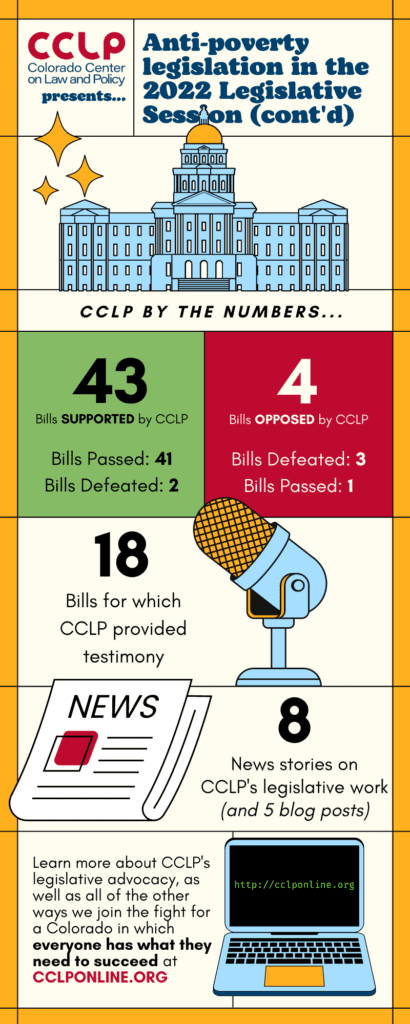

2022 Legislative Wrap-Up

This year’s legislative session has been an intense one to say the least, but with many positive results for Coloradans

experiencing poverty. Major priority bills required research, testimony and support from CCLP — as well as our partner organizations, and our network of anti-poverty advocates — to get across the finish line. Other bills required active opposition on multiple fronts. Many of these bills came down to the wire, only passing in the waning hours of the session, but despite the late nights and furious activity, 2022 has proven another triumphant session for Coloradans.

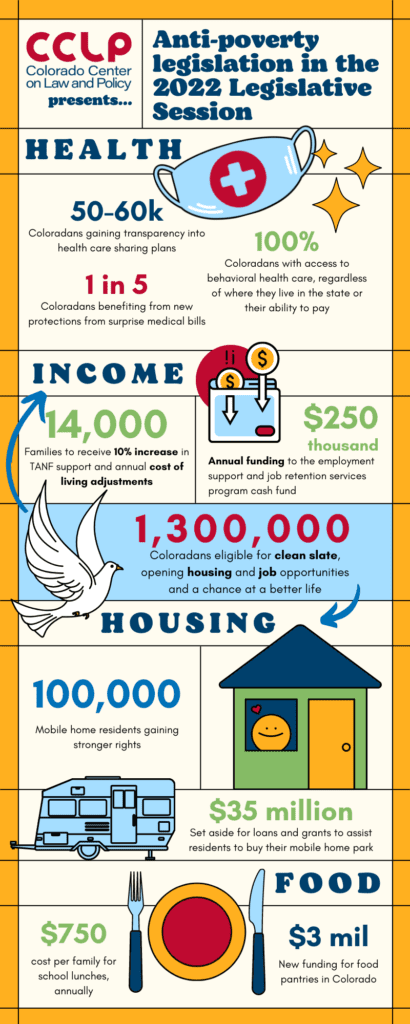

Housing

We are very happy to share that the “Clean Slate” bill, SB22-099, passed out of both the house and senate.

As you heard in our Legislative Preview event in January (link to video), this bill will improve Coloradans’ ability to have non-conviction and conviction records sealed, supporting expanded opportunities for a population that faces enormous obstacles to securing employment, housing, and economic stability.

In coalition with Interfaith Alliance and other state allies, and national groups like Code for America and the Clean Slate Initiative, CCLP contributed hours of research, drafting, and stakeholding to address complex concerns and create a more streamlined sealing process. The hard work of everyone involved appears to have made a difference: the bipartisan bill saw remarkable support in the end, passing the house last week with an incredible 61-to-4 vote. It now awaits the Governor’s signature.

HB22-1287: Protections for Mobile Home Park Residents is headed to the Governor as well. This priority bill addresses concerns of mobile home park residents, by seeking to make modifications to the resident “opportunity to purchase” under CCLP’s HB20-1201, as well as expanding enforcement under the Mobile Home Park Dispute and Resolution Enforcement Program.

Originally this bill had also sought to limit park lot rent increases, a provision that was removed at the threat of veto by Governor Polis. Despite this loss, however, the bill retains crucial provisions to better protect mobile home park residents, such as relocation assistance in case of park closure.

Mobile homes make up a significant percentage of the dwindling affordable housing stock in Colorado. Colorado has about 900 mobile home parks, with 100,000 Coloradans living in mobile homes. Mobile home parks residents average $39,000 in household income, and are disproportionately 65 or older (27%), people with disabilities (39%) or Latinos (29%). A majority of these Coloradans own their homes, but not the land under them.

One provision of HB1287 would have created a $35 million ARPA loan fund, to assist with transition to resident ownership upon sale of mobile home (MH) parks. This provision was split off from the bill and became SB22-160: Loan Program Resident-Owned Communities. Though it became a separate bill, SB22-160 is instrumental in realizing HB1287’s effectiveness. CCLP and others had advocated this set aside for mobile home parks through the Interim Transformation Committee on Affordable Housing. Providing an opportunity for park ownership gives residents more control of the land they live on, more predictability, and more economic stability. We are happy to say that this bill passed house and senate as well.

In coalition with 9to5 Colorado, Colorado Poverty Law Project, Colorado Coalition of Mobile Home Owners (CoCoMHO), Together Colorado, local governments and the extensive Rights for Residents Coalition, we made solid progress with these two bills while cementing a strong coalition to help equalize the power imbalance between Mobile Home Park owners and investors, and those who rent or own the mobile homes in them.

Food

CCLP had been working with Sen. Dominick Moreno to address a key recommendation from the recent CCLP report on SNAP hearings. The drafted bill’s key provision was the creation of a public database to house SNAP hearing decisions, accessible and free to advocates and the general public. Though this bill did not move forward in 2022, we expect to bring another bill in 2023.

In the meantime, CCLP advocated before the Joint Budget Committee (JBC) about the effort by the Colorado Department of Human Services (CDHS) to bring some SNAP hearings “in-house” rather than having those cases heard at the Office of Administrative Courts. The purpose of the move would be to improve timeliness of cases moving through the hearing process in compliance with federal regulations. CCLP’s advocacy led to the JBC’s request for future reporting by CDHS on several factors, including timeliness of hearings and independence of the “in-house” judges. Requiring CDHS to report on outcomes will ensure that this change is not detrimental to those beneficiaries who challenge county decisions that impact their SNAP benefits.

CCLP supported expanding access to healthy meals for all public school students through HB22-1414, Healthy Meals for All Public School Students, introduced late in the session after an earlier bill, SB22-087, stalled due to funding constraints. Led by Hunger Free Colorado, the House bill – passed but not yet signed by the Governor – is funded through a referred measure that closes a tax loophole affecting only those earners who make over $300,000 a year.

Also noteworthy in the fight against hunger are House Bills 1364 and 1380, led by our partner organizations Hunger Free Colorado and Blueprint to End Hunger. HB22-1364 would renew grants to food banks. HB22-1380 makes a number of improvements to SNAP, expanding access through small retailers and farmers markets, and improving technology to manage SNAP applications and caseload. There is new emphasis on locally grown food, fresh food, and culturally relevant food.

Income

The groundbreaking Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF) bill HB22-1259 calls for a 10% increase and annual cost of living adjustment (COLA) for the approximately 14,000 families on TANF. This bill’s approximately $20,000,000 – $28,000,000 annual cost is paid for with American Rescue Plan funds, TANF current block grant allocation and county and state TANF reserves, as well as Unclaimed Property Funds, minimizing the fiscal impact on counties. This bill has been through over two-dozen changes, in part based on County concerns. This bill too now heads to the Governor.

HB1259 also features important provisions to lower sanctions, standardize exemptions from work requirements and from the 60-month time, direct the State Board of Human Service to redesign the “welfare to work offramp” to avoid sudden loss of benefits, and expand outreach and parent input into the program design.

CCLP has continually monitored the efficacy of the Employment Support Services Emergency Fund created as HB19-1107 in 2019, that will expire on 6/30/22. During its 3-year existence the $250,000 per year program has helped 1474 people in 60 different counties who had incomes below the Federal Poverty Level with an average need of $293. We have been the lead organization on the renewal bill, HB22-1230. The bill has passed the legislature and awaits the governor’s signature.

CCLP is collaborating with the Office of the Future of Work at CDLE and representing the Support Services Committee of Skills2Compete on the Digital Equity Subcommittee. We have now been contracted with this Office to conduct community listening sessions and interviews through June 30 to obtain stakeholder perspectives about digital inclusion. CCLP’s Skills 2 Compete Coalition is significantly involved and has influenced the drafting of Senate Bill 140 which includes:

- expansion of work-based learning, digital inclusion, and digital navigators

- the addition of English language instruction and mobile platforms to help workers learn specific work-related English, to help them get and advance in their jobs

- a task force to address the transferability of foreign education credentials under DORA licensing requirements.

In 2013, CCLP ran HB14-1085 to provide funding for Adult Education Workforce Partnerships. At that time, Colorado was the only state in the union to not provide any state funding for adults working to complete high school or to learn English. Ongoing state funding is still less than $1 million per year to serve the more than 300,000 Colorado adults which lack a high school diploma or equivalency diploma. Colorado also has more than 300,000 adults who are not fluent in English. Some one-time funding was added in bills last year and this year.

This year CCLP, in our work with Skills2Compete, joined Spring Institute, libraries, and other Adult Education providers to amend HB22-1009, which sought to renew a “pay for performance” approach to granting diplomas which had passed in 2019, and whose requirements made most existing adult education programs ineligible. According to a Colorado Department of Education, only 50 people obtain a high school diploma last year through the program. Two private companies had collected 80% of the $800,000 in funding under the bill, primarily as payment for partial credits. Participating libraries and community colleges found the funding was depleted before they could apply for reimbursement. CCLP fought for demographic reporting on who was served through the bill, and a change in the funding formula if the program was renewed. This bill ultimately died in appropriations. We will continue to seek a more long-term state investment for those closed out of jobs or promotions due to lack of a high school diploma, or due to not being fluent in English.

CCLP also met with a group of bankruptcy attorneys hoping to modernize and update statuary exemptions from debt collections. Of particular interest to CCLP was the expansion of the definition of “house” to include other dwellings such as RVs, vans, buses and campers. It would also increase the value of a home protected from the current $75,000 to $250,000 in equity to better reflect today’s prices and home value. For older Coloradans and people with disabilities, the exemption for one’s home would increase from $105,000 to $350,000. It would also allow exemption of up to $5000 in emergency savings, UI benefits in their entirety, HSAs, and “any” child tax credit to reflect the new state child tax credit. That bill, SB22-086, was recently signed into law.

CCLP continues to support a fairer tax system. Colorado took a one-year temporary half-step away from the current regressive structure of our TABOR rebate mechanism tiers — in which the wealthiest Coloradans get higher TABOR rebates than low-income Coloradans — with SB22-233. It authorizes flat rebates of $400 per individual, $800 per couple. By the state’s own figures, Coloradans with the lowest incomes — under $10,000 — pay a higher portion of their income in taxes than the wealthiest Coloradans. We joined Colorado Fiscal Institute and Bell Policy Center in testifying against two bills — HB22-1021 and HB22-1125 — which proposed lowering the state income tax rate. We particularly oppose tax cuts like reducing the income tax rate, as roughly one-half of Coloradans (and most older Coloradans) earn too little to owe income taxes (though still must pay many other taxes and fees), and thus receive no benefit. In fact, this population loses part or all of any TABOR refund, while the wealthiest receive the largest reduction under this regressive approach to tax cutting. We anticipate working with Colorado Fiscal Institute and the Bell to oppose a similar measure on the ballot this fall.

Health

HB22-1224: Public Benefits Theft, developed by CCLP in response to a recent Colorado Supreme Court decision, heightens the intent standard used when recipients of public benefits — for health, food, housing and income — are prosecuted for alleged theft. We are happy to announce that this bill not only passed but has already been signed into law by Governor Polis.

Some of the language initially planned for that bill — clarifying that the value of the theft was limited to benefits for which the person was not eligible — was adopted into the expansive criminal justice reform bill, HB22-1257. That bill, too, was signed into law in April.

In partnership with House Majority Leader Lontine and the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative, CCLP developed a bill that requires healthcare sharing arrangements operating in Colorado to report annually to the Division of Insurance. These entities have plan structures that mimic insurance, including premiums, deductibles and cost-sharing, but provide no guarantee of payment, do not cover pre-existing conditions, typically provide no coverage for behavioral health, and may deny payment when a condition is said to violate moral or religious precepts. HB22-1269 has now passed and is on its way to the Governor. (HB22-1198, a competing bill that would have created a safe harbor from regulation for these entities, was killed in its initial committee.)

On its own and in conjunction with behavioral health advocates, CCLP was able to get several amendments — among the many offered and approved — added to the Behavioral Health Administration bill, HB22-1278. The BHA will transform the Colorado system, bringing together federal block grants and state funding, creating regional behavioral health entities to administer funds and enroll providers, and establishing care coordination. That system aims to align with but remain separate from Medicaid and questions remain about how this will affect the care Medicaid enrollees receive. This bill has passed and is headed to the Governor’s desk.

CCLP was involved in several successful efforts around bills that involved hospital and drug pricing.

We successfully testified in support of HB22-1285, a bill that would prohibit collection actions when a hospital is non-compliant with federal price transparency requirements. A February survey found that most hospitals have yet to comply with the federal law, and 16 of the 17 Colorado hospitals surveyed were only partially in compliance.

We also testified in favor of HB22-1122, to prohibit practices by pharmacy benefit managers which disadvantaged Coloradans who qualified for discounted prices under the federal 340B program.

Finally, we testified in favor of a bill aligning the federal No Surprises Act with our state balance-billing law. That bill, HB22-1284, led by the Colorado Consumer Health Initiative, establishes the federal protections as a floor and attempts to preserve stronger protections that are in state law.

All three of these bills passed and are headed to the Governor.

CCLP engaged with other stakeholders on development of HB22-1325: Primary Care Alternative Payment Models, a bill which creates guardrails for the Alternative Payment Methodologies now being developed for commercial and public health plans. The bill establishes timelines for developing quality measures and aims to prevent APMs from disadvantaging populations that are historically underserved and underdiagnosed. This bill now awaits the governor’s signature as well.

CCLP participated in the steering committee for “Cover all Coloradans,” a bill that extends CHP+ coverage to pregnant people without documentation, and extends state-funded Medicaid to children who are undocumented. A Senate Amendment also eliminated premium co-pays for children on the Child Health Plan to eliminate barriers. HB22-1289 has passed as well and we eagerly anticipate the governor signing the groundbreaking bill into law.

CCLP worked with the Department of Health Care Policy and Financing to improve oversight of the state’s Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE), capitated programs that provide an expansive set of services to keep people at home and in the community. CCLP played a major role in 2014-15 during the conversion of Colorado’s main PACE provider, InnovAge, to for-profit status, and raised red flags at that time regarding the need for more oversight of entities that serve this vulnerable population. SB22-203 awaits the Governor’s signature.

In closing…

We are grateful to those who stand steadfast with us against poverty in Colorado, and to those who support the work of this organization. We do not (and could not) do this work alone. We are particularly grateful to those bold legislators who sponsored and fought for the rights of so many Coloradans. Alas, the work never truly ends! As this Legislative Session draws to close, CCLP now shifts its focus to implementation. This can involve rulemaking, education and outreach, informally tracking funding and program implementation and impact, as well as serving on committees charged with . As needed, our legal team will also identify opportunities to improve enforcement of rights created by 2022 and earlier legislation. Simultaneously, we will be working in coalitions and with partner organizations to begin work on our 2023 Legislative Agenda.