A summary of the list of recommendations on the implementation of the OBBBA in Colorado regarding public benefits systems and work requirements.

Recent articles

CCLP testifies in support of Colorado’s AI Sunshine Act

Charles Brennan provided testimony in support of Senate Bill 25B-004, Increase Transparency for Algorithmic Systems, during the 2025 Special Session. CCLP is in support of SB25B-004.

Coloradans launch 2026 ballot push for graduated state income tax

New ballot measure proposals would cut taxes for 98 percent of Coloradans, raise revenue to address budget crisis.

CCLP statement on the executive order and Colorado’s endless budget catastrophe

Coloradans deserve better than the artificial budget crisis that led to today's crippling cuts by Governor Jared Polis.

Working Colorado: When part-time isn’t enough

Colorado is currently enjoying a historically low unemployment rate. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of April 2017, the state has the lowest unemployment rate (2.3 percent) in the nation.

Unfortunately, the unemployment rate alone does not tell the complete labor-market story. Rarely do measures of “underemployment” garner much attention, but they could provide clues into why the sustained economic “recovery” doesn’t feel genuine or robust for many Coloradans.

One form of underemployment is “involuntary part-time employment” — that is, workers currently employed part-time who are both willing and able to work full-time yet unable to secure a full-time position due to slack business conditions, seasonal employment or other factors.

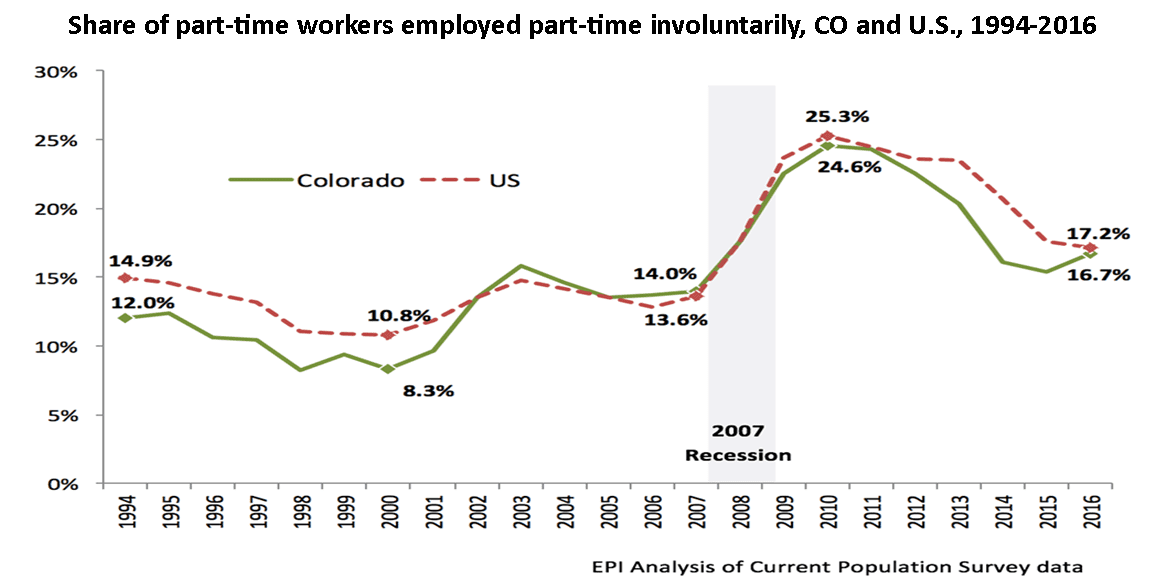

Involuntary part-time employment reached a high of nearly 25 percent of all part-time workers in Colorado at the height of the recession. The rate declined to 16.7 percent in 2016, mainly due to the state’s economy gaining momentum. Fewer workers are indicating that slack work or business conditions are the reason for their involuntarily part-time employment—a reason that is most associated with temporary cyclical shifts in the economy. But while the involuntary part-time employment rate has fallen, it is still slightly above the pre-recession level and higher than historical levels (see chart). Through the late 1990s, less than 10 percent of part-time workers wanted to work full-time.

So if the economy has picked up steam, and it’s clear that the Colorado economy has from the low unemployment rate, why do we still see an elevated rate of involuntary, part-time workers? Some economists argue that the rate remains relatively high because of both cyclical and structural changes to the economy. Structural shifts include practices such as reducing hours to avoid offering full-time workers benefits such as health insurance and taking advantage of lax regulations around “on-demand” scheduling of workers. When combined with a decrease in the supply of workers under the age of 25, these economic trends have led the hospitality, retail and food industries to rely on workers who would have preferred to work full-time schedules and older workers to fill the gaps. Without changes in employment policies, these structural shifts in the economy will continue.

An estimated 98,000 workers in Colorado wanted more hours than their part-time employment offered in 2016. As a share of employed workers, involuntary part-timers in Colorado have doubled since 2000. While shifting to more part-time workers may help employers keep labor costs down, workers who involuntarily work part-time experience problems outside of work.

Often part-time jobs are associated with inconsistent schedules which cause logistical headaches for workers, especially for parents trying to arrange child care. Fewer benefits and lower wages are associated more with the kinds of jobs held by involuntary part-timers than their voluntary counterparts. Since involuntary part-time work is rarely stable, nearly a third experience at least 13 weeks of unemployment annually. This is concerning because a 2012 study found that 25 percent of involuntary part-time workers lived below the federal poverty line versus 5 percent of full-time workers.

An economy that makes it harder for workers to work is not realizing its full potential. In addition to policies that promote job creation, state legislators ought to consider legislation that expands workers’ rights to request minimum and maximum hours and stable scheduling to put involuntary part-time workers on the path to self-sufficiency.

Among these considerations, it seems stable scheduling has emerged as the most popular. In California, state legislators considered Assembly Bill 5 this past year, referred to as the “Opportunity to Work Act,” which would have required an employer who employs more than 10 employees to extend more hours to all currently employed non-exempt part-time workers before hiring another employee. It has been postponed until 2018. This legislation took its inspiration from cities such as San Francisco, San Jose, and Seattle that have passed their own secure-scheduling measures — giving part-time employees in certain industries access to more hours.

In the absence of strong statewide labor protection around scheduling fairness, the New York City Council also recently passed local legislation that would protect fast-food and retail workers — two industries that have increasingly relied on involuntary part-time workers to fulfill their labor needs –from having unfair notice of schedule changes, while providing stable scheduling and a path to full-time hours.

Initiatives like these would create a disincentive for employers to fill their labor needs with multiple part-time workers and counteract the structural shifts in the economy that have contributed to the rise in involuntary part-time work.

-Jesus Loayza